Anne Becker

FIRST SCROLL: IN THE TEXTILE MUSEUM

For John, for my family, for BonnieIn the museum, in the galleries' dim

light, long fibers hang from

the walls, fibers too fragile

for the scant dirt and oil of clean

hands, too fragile for clear incandescent

light. Fibers spun out from the cotton

plant, the banana tree, the linden, wisteria,

grass, the sacred elm, that have crossed,

have wrapped themselves around each

other, darted in and out, taken on color

or resisted, have formed themselves

into garments, undergarments, into bed

covers, into banners that celebrate

the woven life of the child. These cloths

fabricated on small islands in the east,

old pieces fashioned with new threads

into newer and newer work coats, sled-haulers'

vests, socks with split toes, aprons, gaudy robes.

On the back of firefighters' jackets

moon's rabbits stand up like men

pounding rice for rice cakes, head bands

around their heads, smoke clouds billow

across the shoulder's sky, lightning bolts

flash on the sleeves. On the inside

a red peony blooms like a torch fastened

to the man's skin. Bed clothes too:

a comforter mimics a robe, split open

at the spine, an extra panel inserted,

the sleeper has slipped her arms into

the coverlet's wide sleeves, back of the robe's neck

tucked under her chin--what dreams sail under the blue

skin of the sea? Where rabbits leap from curling

wave crest to wave crest, pale grey pelts

curling like foam, fearless, fool-hardy rabbit

wits that crossed the ocean from island to island

jumping from slick shark's back to shark's back,

jeering the living bridge before they touched shore.

Or foretell a large family, so many children

each separate, each joined by discontinuous threads like

foam, like watery spray, like the sharp scent

of smoke carried on the air. Or that bridge of

stars that spans a whole ocean of night sky, divides

those who love each other, through all these piercings,

these bindings, deep indigo field pricked and pricked

with light until a wash of light weaves a

road, a track, needle's path in the mind's eye. So that one

day, the seventh day of the seventh month, any

miraculous day, each year, they fly, they cross on

sources of light, they reach, meet

warm finger tip to finger tip in the blue air. Doors open,

we walk out into motes of red-gold November light.

The museum bursts into flame.

FORCES OF NATURE

Questions like: do angels have wings, these are the kinds of things

we demand answers to--and do they really fly into our dreams

with their array of doors, towers, baskets, rivers, radiators

and snakes just to show how we've been bad again;

don't they have anything good to say;

why do they appear in pillars of smoke, pillars of light;

are they afraid to show their face, or is the task

merely to keep us guessing--do they bite?

and how many of these infernal creatures are dancing

to beat the band on the stainless steel dance floor,

manic as usual at God's bidding, and why doesn't he do his own

dirty work, anyway, why doesn't he fight his own battles

and not draft us and his poor angels to blow until we're blue,

why do we continue to hope we were made in his own image

when all we know for sure is

we can dance like angels and we don't stop

whispering, "fools, what fools," as we float away.

SEXUAL SELECTION

Today I entered the great sub-kingdom of the Vertebrata;

all day I have studied fish, dissected them, read about them

in books and journals, in letters from my expert correspondents

who patiently answered all my detailed questions, compared

male and female fish, wondering always what causes the differences

between the sexes. I am mad with delight having a whole new class

of creatures to consider. At luncheon I could hardly eat my soup

for thinking of the feathery gills, pectoral fins, the hooked

jaw of the male common salmon. Now at night, I lie in bed awake

while Emma sleeps the good, well-earned sleep of the wife

and mother; she snores softly, and pictures of fish as accurate

as Mrs. Cameron's photographs appear in my mind as if I dreamed

awake. Mr. Warington's loving estimation of the male stickle-

back--he says it is beautiful beyond description--returns

to me and Emma swims by, a gigantic pale fish, her scales shiny

and wet, the quick flick of her fins as she swims off, smiling

slightly at my enthusiasms. And I imagine myself a male fish.

I dart around her in every direction, and then back to the nest

I have made for her. I return to her again; she continues her

strong, steady, idle swimming, amused by my ardour. I push her

with my snout, pull her by the tail and side-spine, I am mad

with delight, I will do anything. I am bright green and blue,

belly and throat carmine, my scales are lustrous like metal,

and I feel my skin translucent, thin, my fishy body slippery,

aglow with an internal incandescence as if my love resided

hot in my simple heart, in my muscles, all my organs, in my tail

and fins, even in my bones, not merely in my mind--

the thoughtless love for the female of my kind.

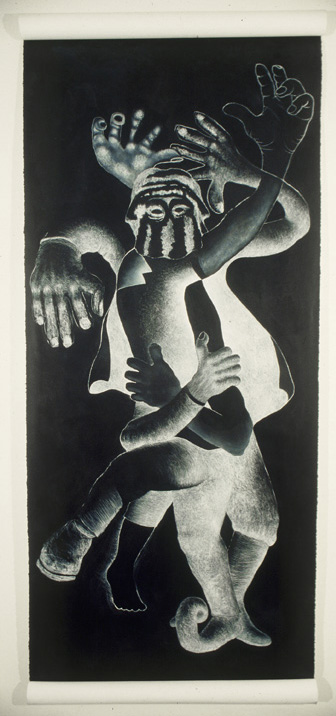

Richard Dana

Deep Dark Dance

Conte crayon, acrylic on paper: 102x45"; 2002

see more work by Richard Dana

VARIATION

Eight years I laboured at my task, at the dissection

and description of my Cirripedes; although in that time

two entire years were lost to bouts of illness

when my stomach was so racked with pain I could not

work. Whole days went by when I could do no more

than lie on the sofa while my dear Emma read to me,

and if I slept she kept on reading aloud, believing

the sound of her voice helped me sleep. Or I wentfor the water cure, days spent wrapped in cold,

wet sheets and this enabled me to work again--although

how it helped I do not know. In those eight years

how I came to hate them, these creatures with their

shells, some stalked and some attached directly to a rock,

or a whale, or to the bottom of boats, whatever is awash

in water. And how, at times, I felt such joy and wonder

as when on my Beagle voyage I discovered in Chilea new form which differed so from all the others

that it required a new sub-order for its sole

reception. Now when I was young, my father and

my masters considered me an ordinary boy; I confess

I did not care much for the classics nor my assigned

subjects in school, but in a fit of unjust anger,

my father, usually the kindest man, declared that I

cared for nothing but dogs and shooting and rat-catching; I would disgrace my family, he

predicted. While I have no great quickness of wit

and apprehension, and no more inventiveness or

common sense than any successful doctor or lawyer,

and my memory though extensive is hazy,

and my power to follow a long and purely abstract

train of thought has its limits, on the favourable

side of the balance, I think I can truly sayI am superior in noticing things that easily escape

attention, my industry could not have been greater

in the observation and collection of facts. Since

my earliest youth I have had the strongest desire

to understand when I observed: to bring order

to the chaos of fact. This is how I came to

undertake this mammoth task--to understand this one,

my Balanus arthrobalanus, I had to study all.So for those eight years it was as if

a slow current flowed through Down

House depositing barnacles that day after day,

under scalpel and microscope, gave up their secrets.

In those eight years my children accepted barnacles

as a common household item, if not a necessity,

their dissection as a usual occupation.

My description of a larval cirripedewith six pairs of beautifully constructed

natatory legs, a pair of magnificent compound

eyes, and extremely complex antennae caused them

much amusement, an advertisement for barnacles,

they quizzed me. During those eight years I

discovered the cementing apparatus--although

I blundered dreadfully on the cement glands--

I came to know barnacles as a parent knowshis children, how each is alike, how

each is different, as if one had got their mother's

hands, another the shape of their father's head. What

diversity there is, even in these simpler creatures,

and for me how pleasant is variation. I discovered too,

perhaps the most remarkable barnacle of all: among these

animals most are hermaphrodite, carrying out the duties

of both sexes. But this strange one, I suspect, is the mostnegative of creatures: males who have no mouth, no

stomach or thorax, no limbs or abdomen, they consist

wholly of the male organs in an envelope. What

started as a little zoology grew and grew

into a great beast for I could not do less--

despite illness and the interruption of children

I hung on to my study like grim death--how

else had I the right to examine this question:what accounts for variation,

unless I myself described many

species. No, I could not abandon my sea

creatures in midstream, I had to swim doggedly

through them all. What I have learned now fills

four volumes, but in truth never has a mountain

of labour brought forth such a mouse--

I do not know if it was worth it.That there are laws of inheritance I have no doubt,

but what they are I have yet to find out.

DAUGHTER'S TRIBUTE

I received her last letter: "Sick on Sunday;

well again today, Monday." On Thursday night

she wound her watch as usual, placed it on the bedside table,

laid her head back on the pillow, closed her eyes,

and never woke again in this world. Bessy, of course,

was with her, was the last to see her alive, help her

unpin her hair, wish her good night. The next morning, it was

her body and not her body that lay in her bed. When I arrived,

it was my mother and not my mother I saw, dressed

and laid out, the hands motionless on the chest.

Frank, George, Horace, Bessy, all there before me.

My mother was all things good. Bessy is, of course,

completely distraught; she cries all day long

and can do nothing. Her hands are constantly aflutter--

like a pair of squabbling sparrows. I am angry.

What does God think He is doing?

I have arranged everything, found a minister with common sense,

settled my mother's affairs. I cleaned out her desk,

decided what to destroy, what to save. All the letters she kept,

her diaries, everything that may contain her spirit

I will take. Bessy can have her shawls, her caps, the furniture.

My mother was all things good. In her youth

she was gay and carefree, not above a practical joke.

But I remember her as grave, beset by the anxieties

of our many childhood illnesses and my father's poor health.

Reserved: to strangers she appeared stern, aloof.

I have no clear recollection of her playing with us--

the jokes, the merriment all came from my father.

But now a picture comes to my mind of the parlour furniture

pushed to one side, the rug rolled up, and a troop of

little children galloping to a tune of her own composing.

She never minded childish messes. And she sang to us,

nursery songs--"When Good King Arthur ruled the land..."

"There was an old woman as I've heard tell...

and if she's not dead she's living there still."

Courageous, rash even, in what she let us do.

William was taught to ride without stirrups and thereby suffered

several bad falls. George, at ten, was allowed to go

the twenty miles from Down to Hartfield alone.

And I, too, wandered the woods and lanes by myself

which at that time was not quite safe for a little girl.

My mother was all things good. Calm, serene:

she understood that life's uncertainties

did allow for hope. Always comforting,

she never offered false comfort, false praise.

Fair, honest, blunt: an enthusiastic guest once thrilled

how she must enjoy watching Father conduct his experiments--

"No, I don't." My mother was all things good.

She was definite in her religion, in all her opinions.

Shakespeare, Milton: tiresome.

Tennyson: less so. Coleridge: revolting--

a mixture of gush, mawkish egotism and humbug.

So I had to learn poetry from my husband.

Although poets are, I fear, a lazy lot,

not as accurate as they should be, or perhaps, a bit stupid.

I have not found one poem that could not be improved.

Her sense of duty was strong: she had a large clientele

in the village. But I doubt whether she was any real help

since she never inquired closely about them

and many were people of bad character.

She didn't care much for art or higher education.

(She never tried to get the best teachers for us.)

What she cared for was comfort and Nature and affection.

She made the most of little pleasures: her delight

at the first taste of spring. I do remember clearly

that summer afternoon she called me to the window

to watch two blue titmice leapfrog over each other on the lawn.

I will hunt the stinkhorn in her honour. And, of course,

she thought it abominable to be brutal to animals.

Mounting a crusade to abolish steel traps used in game preservation,

she offered a prize for the design of a humane trap, but no new

da Vinci, no James Watt came to light and the reward went unclaimed.

My mother was all things good. She would do anything

for her servants and their relations. Each summer

she invited the cook's blind daughter to spend

a month with us and they discussed life in the Asylum.

My mother was all things good. She was

splendid in grief: when my father died, to us

who knew how she lived in his life, how

she shared each moment as it passed, she seemed

wonderfully calm, perfectly natural. Only in letters afterwards

could she find words to express her sorrow. And even she was amazed

she could enjoy life still--the good summer weather,

flowers in bloom, the clear bright colours of their petals.

She suffered her desolation alone, not wanting to be thought of

or considered, but to be left to rebuild a life as best she could.

And rebuild it she did, setting up a winter home in Cambridge,

making new friends. And now that the burden of love

she had taken on gladly when young was lifted somewhat

her sense of mischief returned. "I attended the downfall

of the great elm over the Lodge, and a grand sight it was,

especially when it took matters into its own hands and crushed

a good-sized sycamore instead of going the way they were pulling."

Or when she told me how the explanation she gave Bernard

of the play Electra shocked Price the butler.

"Is it nice?" Bernard asked. "Oh, yes, very," she replied.

"What is it about?" "A woman who

murders her mother." No--I understand nothing.

My mother was all things good. She was the one who taught me

our God is a benevolent God. Then what about this suffering?

He made the darkness pavilions around Him, dark waters,

and thick clouds of the sky. I understand nothing.

But what I cannot swallow is: I had no chance to say good-bye.

Born in Chicago, Anne Becker grew up in Silver Spring in that distant era before the Beltway was built. She has lived in and around Washington, DC most of her life. For 17 years, she produced Watershed Tapes, audiocassette recordings of major American and international poets reading their work. Becker's poetry, fiction, interviews and reviews have appeared in Gargoyle, Antioch Review, Ear Magazine East, Southern Poetry Review, Sing Heavenly Muse!, Washington Review, Washington Jewish Week and other journals. In 1996, her book, The Transmutation Notebooks: Poems in the Voices of Charles and Emma Darwin, was published by Forest Woods Media. An excerpt from the book, translated by poet Teresa Madrid, appeared in Calicanto, a literary publication from Manzanares, Spain. Becker teaches in the Maryland Poets-in-the-Schools program as well as at The Writer's Center. In addition to providing poetry tutorials for adults and children, she conducts a workshop, Writing the Body, for those who have experienced life-threatening or chronic illness as patient, care-giver, or family member.

Published in Volume 5, Number 2, Spring 2004.

Read more by this author: The Museum Issue