|

|

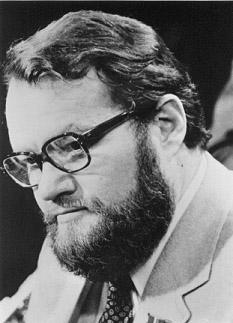

Grace Cavalieri on ROLAND FLINT

(1934 - January 2, 2001)

I

don't think the dead go anywhere at all. It doesn't seem as they are very far

away. I think eternity is in my living room and I can reach out and touch it

at any time. W.S. Merwin says Heaven goes on without us, but I certainly feel

it around me, and can bring the dead back by opening a book. Roland Flint's

voice is still on the page. It didn't go anywhere at all.

I

don't think the dead go anywhere at all. It doesn't seem as they are very far

away. I think eternity is in my living room and I can reach out and touch it

at any time. W.S. Merwin says Heaven goes on without us, but I certainly feel

it around me, and can bring the dead back by opening a book. Roland Flint's

voice is still on the page. It didn't go anywhere at all.

Anyone who ever heard Roland read would never forget his speaking voice. Robert Pinsky claims that there is a pillar of language left from the poet that stays inside us and when we read that poet we bring forth the spirit, the voice. Of course this has been called the breath of God. Surely we can still hear that deep resonance, and the way Roland achieved a harmonic structure while he told a story, or an anecdote, or a lesson. He told stories with the sound the heart makes, and this is something the reader cannot turn from, and cannot forget. Roland Flint gets right next to his reader, and for this reason he has earned a permanent place in American Letters.

Anyone who ever read Roland knows he has a no-nonsense approach to the poem. This may have come from growing up and living so close to the earth, as a young person. Just as story telling comes from the grain, Roland Flint used the sounds of the colloquial and the marvelous, to become America's preeminent narrative poet.

If we want to teach "voice" in the classroom, there is no one better poet than Roland Flint to use for teaching. The direct honest approach to the line is what we hope students will achieve. How do we write without artifice? Roland told his truth and we loved to hear it. Whether he wrote about a simple felicitous dinner hour with his wife, or the death of a child, his poems are designed as well as spoken. Poetry may be the highest form of locution, but only if it is spoken softly enough so it can be heard.

Roland Flint's canon of work spans a multitude of human experiences. He is famous for a prose poem about oysters, and a poem about taking his kids to the zoo where animals are mating, and, of course philosophical poems, reveries that tell us how he felt. Such a breadth of subjects could only come from a spirit too large to be limited. His speech patterns go from folkloric speech to classical meditations. There is athleticism in his work that reveals a great comfort with language and produces energy beneath the line. This is Flint.

Roland was no different in person than he was in print. We could go to him with our own problems (he called them "hooks under the water") and our complaints ("write about that".) He was connected to others writing around him. Roland would often recite others poets' works at his readings; this was another display of his range and knowledge. He worked from a huge platform in American literature, drawing on the Masters to lift his own Mastery.

He taught us a big lesson by his public presentations. May God help the person who made noise in the audience, for he would stop reading until poetry was respected. This demonstration taught other poets that this is where he drew the line. The poet was not a piano player in a cocktail lounge. Every way Roland lived showed us that this poetry was an honorable profession, and therefore it was a profession to be honored.

Roland was the most robust person in any poet's audience. He was the one we wanted iat our readings, with his large laugh and tremendous hydraulic power responding, and giving complete approval, urging us on.

He was an annual guest poet at St. Mary's College of Maryland, and for the last 10 years of his life, he was a "regular" at Michael Glaser's poetry festival, teaming with Lucille Clifton to give unforgettable poetry concerts (the two laureates). He even appeared the May before his death in January. He was thinner then, and his large voice was thinning also. Yet he loved working with the students--it was where he wanted to be. Even here, it was Roland's practice, to wake at 5 a.m. each day to write a morning poem, then return to sleep until 8. He said this was one of the benefits of retirement and he loved the early dawn.

Just as sure as dawn gives way to day, day gives way to night, and all voices will be quiet but for the page. Every time we remember someone we bring him back from the dead. We just open any one of Roland's books and we will hear Roland Flint speaking.

Here is a meditative poem, where Roland's phrasing, rhythm, and poetic temperament are beautifully displayed.

WHAT I HAVE TRIED TO SAY TO YOU

That there are ways to love the life you haven't had,

ways to forgive the one you have.

That while your brother wasn't killed

to test anyone, his death is,

somehow, allowed by the mystery

requiring our lives to have this

permanent pull at the middle.

Our lives are what they have been: unrevisable,

changed only in our responses,

if we are still ready, somehow,

for the next day, the next

person, poem, chance, even prepared,

however unready, for the next death.

Can we permanently grieve the boy

without hating what has become of him?

What has become of him?

He has returned to mystery,

the same one that is our life,

mine and yours this morning,

the continuing shapes we never see

up there, this afternoon, tomorrow:

so he is already, ahead of time,

in everything we do. I feel it, often,

that I am living my life in part for him,

not permanently dead in us, but telling

how we'd rather he had lived than not.

Remember our game of listening in the park

to hear the woods fill up with sounds,

birds, mostly, from farther and farther away

the longer we listened. He seems now

especially to have listened,

raptly, eyes closed, as if to singing,

as if he were entering the song,

and like the way he usually walked

far ahead of us or far behind -

already gone to his own music.

When I think how long it is

since he has entered all silence,

it takes me by the heart to think

those sounds like light have stayed

in whatever we are left to be.

That songs we heard those days

are from the place he's gone away to,

a singing in the mysteries connecting us,

if we can stop and be quiet and listen.

(Easy, LSU Press, 1999)

Poetry is the permanent record of human sensibilities, but only if it is powered by the breath of sympathy. The experiences and anecdotes in Roland Flint's life, and in his poems, carry others with him in the greatest tradition, and move literature forward into future centuries.

_______________________

Three friends remember him:

Poet Philip Jason, Professor Emeritus, US Naval Academy, " He loved to explore the frailties and surprising strengths of characters most others would call "losers," noting the capacity for nobility in unexpected places. He celebrated the ordinary miracles of daily life."

Poet Michael Collier, Director of the Breadloaf Writers' Conference, and Professor, University of Maryland, "The cores of his poems are like small prayers, and they have the attitude of prayers. He was really a secular poet who was able to find an evidence of God's grace everywhere."

Reed Whittemore was the second Poet Laureate of Maryland and preceded his good friend Roland Flint in that office. Reed's wife Helen once asked Roland for his "first poem" (what a wonderful request) and here are Reed's words: "Roland instantly obliged with 'First Poem,' inscribing it to Helen, with thanks to her for asking. That poem is in his latest collection, Easy, reprinted from the North Dakota Quarterly. I think it can be thought of as not only a first but also a warmly definitive account of what a poem's ingredients remained for him as an adult. I won't elaborate on what the child with his six shooter, the woodcraft teacher Mr. Binas, and all the Binas daughters conceived to be a poem--or better, a poet--to be, but it does seem fair to say that Roland lived his remarkable adult poet-life with that communal vision of the dimensions and spirit of the art at work in him. A fine warm vision it was."

_______________________

Roland Flint was born and raised in Park River, North Dakota, in 1934, the fourth of six children. He was the son of a farmer who lost his property during the depression and became a farmworker. In this poem Roland talks to his mother foretelling of life and death.

2-26-91

Well, mother, tomorrow night

I will be born, if this were 57

years ago, and you were 29.

Twenty-nine! How young you

would be to me now, mother!

A girl. Were you still

a girl at 29? - having your

fourth baby, your first after

the miscarriage, me?

If I'm thinking of you more,

am I getting ready to be born

again or do I miss you

from reading Juan Rulfo,

who lets the dead

son and mother talk

the way we did so long,

a month before you died,

seven years, 5 months

and 8 days ago, almost 50

years after that night

we beat the doctor

by 25 minutes or so.

Remember? I don't, but

you remembered it to me.

Now I remember to you,

everything, the 40 watt bulb,

the winter, your holding me

aside till the doctor

came to cut the cord.

(Easy, LSU Press, 1999)

Roland was a former football player. After he "flunked out of college," as he put it, he served two years as an enlisted man in the Marines in post-war Korea, then returned to attend the University of North Dakota, where he began writing poetry and received a B.A. in English. This was followed by an M.A. from Marquette University, and a Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota. His doctoral dissertation was on Theodore Roethke. He claimed that his own work was greatly influenced by Roethke, and by another great American poet, James Wright. Wright was a personal friend.

In 1962 he married Janet Altic. They had three children, Elizabeth, Ethan, and Pamela. In 1968 Flint accepted a position at Georgetown University and the family moved to Washington, D.C. He taught literature and writing at Georgetown for 29 years until retiring as Professor of English in 1997. Often he headed the reading series, bringing poets to the college to perform for his students. He was honored with Georgetown's "Bunn Award," for faculty excellence.

In 1972, a tragedy shattered his personal life when the Flints' six-year-old son Ethan was hit by a car and killed in front of his home. Here is one poem resulting from that tragedy.

A POEM CALLED GEORGE, SOMETIMES

Before he died, my son made up this poem:

..........There once was a boy

..........Who went to the market

..........And bought some hot chocolate

..........And put it in his red pocket.

I said, it's fine, Ethan, especially that red pocket -

what do you call it? He said, what do you mean? Most

poems have names, I said. And he said, ah * George.

And when he heard me repeating the story

of his

poem and of its naming, he said, sometimes I call it

Jack.

That wasn't his best poem.

Like me he didn't in-

tend his best poem: we were walking beside the tidal

basin just past dawn, the cherry trees in bloom, the sun

bright and the blossoms reflected in the still water. He

pointed down and said,

..........Look, water in the trees

I thought I would steal the title, my lost boy, to be

with you in your poem, but it's made me see I'm going

to have to write that poem I do not want to write, named

Ethan.

(Resuming Green, The Dial Press, 1983)

Flint's daughters, Elizabeth and Pamela, also appear often in his poetry. Roland and Janet divorced soon after Ethan's death. Roland later married Rosalind Cowie, who was with him for 21 years during his rise in American letters, and then through his illness and his death.

Roland Flint's poems have appeared in our country's leading periodicals such as The Atlantic Monthly, The Chicago Tribune, The Denver Quarterly, The Georgia Review, The Minnesota Review, Poetry Northwest, Prairie Schooner, Salmagundi, Tendril, Tri-Quarterly, The Washington Post; and, many others, including numerous anthologies and broadsides. He was a friend of Garrison Keillor and his poetry was featured on Keillor's radio series. He published three chapbooks and six books of poems, including Stubborn, which was selected for the National Poetry Series in 1990. His last book was Easy (Louisiana University Press, 1999).

Roland loved to travel and especially loved visiting Italy. For several years Roland studied Bulgarian, and became fluent enough to assist in the translation of three books of poems from Bulgarian to English. In 1994, his own book, Pigeon In The Night appeared in Sofia, Bulgaria, a bilingual edition of selected poems from Fakel Press.

He was a Silver Medalist in the CASE National College Teacher of the Year Award. In addition to being a Professor at the University of Maryland, he was on the faculty of the MFA Program at Warren Wilson College in North Carolina, and was a Poet in Residence at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon, and taught at the National University of Singapore. Roland was on the poetry faculty at the Breadloaf' Writers' Conference. For many years he co-edited the periodical Poet Lore, which is housed at the Writer's Center in Bethesda, Maryland.

His awards include grants from the Maryland State Arts Council,and the National Endowment for the Arts. He served as a judge and as a panel member for the NEA. He received honorary doctorates from North Carolina Wesleyan College and from the University of North Dakota, his alma mater. In 1995, Roland Flint was named Poet Laureate of Maryland by Governor Parris Glendening. He died on January 2, 2001 at age 66.

Of the many words written and spoken about Roland Flint, I've chosen two poems in his memory, by his friends Ernie Wormwood and Linda Pastan.

FOR ROLAND FLINT ON HIS BIRTHDAY, 2/27/03......By Ernie Wormwood

So reverently irreverent, so hot, so cool,

so wondrously flawed, so eager for words

and women and baseball and jazz.

Flint was fun.

He rescued me once at Camden Yards.

I was a new orphan, weeping for my Dad

who loved baseball at the Statue of Babe Ruth.

He was in the Will Call line. I walked over

and spilled it all-grief, fear, pissedoffedness.

His own loss of his beloved rose up in his face,

for his mother, dead, get this, fifteen years.

I was saved, my grief was welcomed.

We stood there in Will Call weeping for

Babe Ruth, my father, his mother, his little son.

The last time I saw him was at a Literary Festival.

He asked me to take him to dinner at a seafood place.

We had rockfish and french fries and beer,

more weeping and then we drove around

listening to Ella sing "Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered."

You have the dirty version, he said. They made her record another

one.

This is the good one.

That night Roland told me he hoped someone

would remember him the way I remember my father.

I told him someone would.

I told him it would be easy.

_______________________

RIVERMIST: FOR ROLAND FLINT by Linda Pastan

When the kennel where my ridgeback died

some thirty years ago

wrote to ask for my business again,

offering us one free night's board

for every three nights paid, I looked

at that name on the envelope, Rivermist,

imagining they were writing to say

that Mowgli was somehow alive,

the swordlike blade of fur still bristling

on his back; that he had waited

all these years for me to pick him up.

And though I've had four dogs since,

a small one at my feet right now, each

running too swiftly through his life and mine,

I could have wept, thinking of rivers and mists -

how in their wavering shadows

they had prefigured and concealed

the losses to come: mother and uncles, friends,

and Roland now, so newly dead, who

on the flyleaf of an early book once wrote,

in his careful, redemptive hand: with love

for Linda and Ira, and for Mowgli.

_________________________________

Books by Roland Flint

Easy (Louisiana State University Press, 1999)

Pigeon (North Carolina Wesleyan College Press, 1991)

Stubborn (University of Illinois Press, 1990)

Sicily (North Carolina Wesleyan College Press, 1987)

Resuming Green (The Dial Press, 1983)

Say It (Dryad Press, 1979)

The Honey (Unicorn Publications, 1976)

And Morning (Dryad Press, 1975)

____________________

Radio and Video Programs with Roland Flint

"The Poet and the Poem" with producer/host Grace Cavalieri. Archives housed at the George Washington University Gelman Library, Grace Cavalieri papers, Box 8, Item 37 and Box 14, Item 212.

"The Poet and the Poem from the Library of Congress," 1989, Witter Bynner Series, produced by Grace Cavalieri, housed at the Library of Congress Archives and Pacifica Program Service.

"Voice as a Bridge," video cassette produced by Grace Cavalieri with Goethe-Institut, accompanying book (anthology of four German poets and four American poets) published by Forest Woods Media Productions, Inc. (aka The Bunny and the Crocodile Press), 1996.

"American Poetry: Live" with Roland Flint and Grace Cavalieri, October 1981. Video produced by The Howard County Poetry and Literature Society.

____________________

Web Links

Roland Flint

This comprehensive author's site reprints a wide range of poems, as well

as including audio files, biographical information, reviews, pictures, and remembrances.

http://www.rolandflint.com

HoCoPoLitSo

The Howard County Poetry and Literature Society hosts a cable TV series, "This

Writing Life," which has included interviews of Roland hosted by Lucille

Clifton and Linda Pastan, and interviews of Lucille Clifton, Carolyn Forché,

W. S. Merwin, Ann Darr, Robert Hass, Terence Winch, Michael Collier and Josephine

Jacobsen hosted by Roland. Tapes available for sale.

http://www.hocopolitso.org

The Atlantic Monthly

The March 2002 issue includes an audiofile of Linda Pastan reading her poem,

"Rivermist: For Roland Flint"

http://www.theatlantic.com/unbound/poetry/antholog/pastan/rivermist.htm

New Bay Times

Transcription of an interview with Roland by Sandra Martin, published in the

April 16, 1998 issue, entitled "Maryland's Poet Laureate: From Potatoes

to Poetry, Roland Flint Digs Into America."

http://www.bayweekly.com/year98/lead6_15.html

Louisiana State University Press

Catalogue and ordering information from the publisher of Easy.

http://www.lsu.edu/lsupress/catalog/spring99/99spr_book/flint.htm

Calvin College

Real audio tape of a January 18, 1999 radio show featuring Garrison Keillor

and Roland Flint, called "An Abecedary of Poetry."

http://www.calvin.edu/january/l999/keilflin.htm

Georgetown University

Obituary from The Hoya, the newspaper of the school where Roland taught

for 29 years, from January 19, 2001.

http://www.thehoya.com/news/011901/news8.htm

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rosalind Cowie for permission to print "A Poem Called George, Sometimes," "2-26-91," and "What I have Tried To Say To You." Thanks to Ernie Wormwood for permission to print "For Roland Flint On His Birthday, 2/27/03;" and thanks to Linda Pastan for permission to reprint "Rivermist: For Roland Flint" which first appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, March 2000.