LANGSTON HUGHES TRIBUTE ISSUE

Langston Hughes in Washington, DC: Conflict and Class

Essay by Kim Roberts

Langston Hughes lived in Washington, DC for a very short time: one year and four months. During that entire time, he was depressed and unsettled. And yet that time, from 1924 to 1926, was extremely important in the poet’s early development.

While residing in DC, Hughes won his first poetry competition, and gave his first public readings. He got a contract for his first book of poems from Alfred A. Knopf in New York, finished his book manuscript, and published The Weary Blues in February 1926. He also wrote most of the poems that would appear in his second book, Fine Clothes to the Jew. He developed friendships with prominent writers and intellectuals such as Alain Locke and Carl Van Vechten, and also with numerous younger writers. More than anything else, however, Washington, DC was important to Hughes for how it solidified and deepened his commitment to the African American working class, which would influence his writing for the rest of his life.

Hughes arrived in November 1924 to join his mother, Carrie Mercer Hughes Clarke, and younger brother Gwyn, nicknamed Kit, in the home of his cousins. (Kit was his father's stepson by a different marriage, so he was not related by blood to Hughes, but Carrie raised Kit and they considered themselves brothers.) When he arrived in Washington, Hughes was 22 years old, broke, and recently returned from a trip to Africa and Europe. His cousins were prominent in Washington's social scene, descendents of John Mercer Langston, the first African American to graduate with a masters degree in theology, and the first African American to be elected to public office (township clerk of Brownhelm, OH). Langston had served as dean of Howard University Law School, Minister to Haiti, and held a one-term seat in the US House of Representatives.

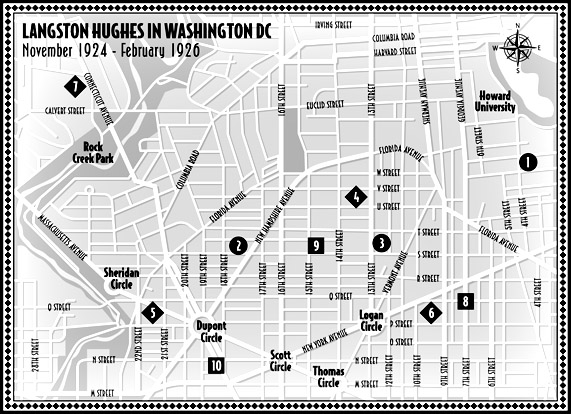

See Site #1 on the map: The Langston House no longer stands. Once located at 2213 4th Street NW, that site is now a parking lot on the Howard University campus.

His cousins, hearing that Hughes was a poet, expected that he would be scholarly like his great uncle. At their urging, he met with other prominent Washingtonians, including Mary Church Terrell (to try to get a job as a page at the Library of Congress), and Kelly Miller (to try to get a scholarship to Howard University). Both of those meetings were unsuccessful. Hughes's first job in DC was for the weekly newspaper The Washington Sentinel, also a respectable job, but he quit soon after his hiring because he disliked selling advertisements.

See #4 on the map: The office of The Washington Sentinel still stands at 1353 U Street NW, now converted to an art gallery. The tile work at the top of this building depicts an old printing press.

His cousins' expectations for his behavior were very restrictive, and Hughes and his mother soon found themselves at odds with their hosts. Hughes would later write in his autobiography, The Big Sea:My mother and kid brother were in Washington. This time, she wrote, she and my step-father had separated for good, and she had decided to come to Washington to live with our cousins there, who belonged to the more intellectual and high-class branch of our family, being direct descendants of Congressman John M. Langston. She asked me to join her. It all sounded risky to me, but I decided to try it. My cousins extended a cordial invitation to come and share their life with them. They were proud of my poems, they said, and would be pleased to have a writer in house....I arrived in Washington with only a sailor’s peajacket protecting me from the winter winds. All my shirts were ragged and my trousers frayed. I am sure I did not look like a distinguished poet, when I walked up my cousin’s porch in Washington’s Negro society section, LeDroit Park....Listen, everybody! Never go to live with relatives if you’re broke! That is an error.

The final break with the cousins came over Hughes's second job. He took work at a wet wash laundry for $12 a week, a much higher salary than he could earn at the newspaper or as a page. His cousins believed this type of work was beneath the family and unsuitable, but Hughes seemed to like the job’s lack of pretensions. Hughes wrote that the job was an easy walk from his next home. Possibly this was the Paramount Cleaners (which, only seven blocks from his next address, was the closest laundry listed in the DC City Directory for 1924).

See #5 on the map: The Paramount, at 2129 P Street NW in Dupont Circle, no longer stands, and is now the site of a hotel.

Hughes and his family moved to an apartment in a two-story brick townhouse. The house was owned by Sol Davis, a laborer, who lived on the ground level.

See #2 on the map: Located at 1749 S Street NW, this house is still a private residence.

In The Big Sea, Hughes wrote:We located two small rooms on the second floor in an old brick house not far from where I worked. The rooms were furnished, but they had no heat in them, so we bought a second-hand oil stove, which we had to take turns using, carrying it back and forth between my room and my mother’s room, since we couldn’t afford two oil stoves that winter.

This unsatisfactory arrangement affected his writing:

I felt very bad in Washington that winter, so I wrote a great many poems. (I wrote only a few poems in Paris, because I had had such a good time there.) But in Washington I didn’t have a good time. I didn’t like my job, and I didn’t know what was going to happen to me, and I was cold and half-hungry, so I wrote a great many poems. I began to write poems in the manner of the Negro blues and the spirituals.

In response to the rigid class segregation in the African American community, Hughes began to spend more time in the city's working class neighborhoods. This was partly in response to his experience with his cousins, and partly in tribute to Jean Toomer.

The two main commercial districts for African Americans in 1920's DC were U Street and 7th Street, and the two could not have been more different. U Street was refined, home to fancy nightclubs, theaters, and restaurants that catered to DC's prosperous and proud middle class. Some institutions that still stand on U Street include the True Reformers Hall (1200 U Street NW, in the 1920’s home to the city’s African American National Guard Unit, the Knights of Pythias club, and a second floor auditorium that seated 2,000, the site of Duke Ellington's first paid, professional gig with his band "Duke's Serenader's"), and the Lincoln Theater (1215 U Street NW, then a classy, first-run movie theater under African American management with 1,600 seats). U Street also boasted the only bank in the city that would lend to Negro patrons (The Industrial Bank of Washington, still standing at 2000 11th St. NW), the first African American-owned Western Union office, Addison N. Scurlock's elite Photography Studio, and numerous social clubs and societies. Dubbed the "Black Broadway" by Pearl Bailey, U Street's famous night clubs included the Bohemian Caverns (2001 11th St. NW), and Republic Gardens (1355 U St. NW), both still standing.

Toomer was the first younger African American writer to publish a book during the Harlem Renaissance period, and Cane electrified Hughes, exciting his own ambitions to publish. Toomer was raised in a house on U Street (1341 U Street NW, no longer standing, now the site of a multi-story office tower called The Ellington), and his own family line was quite prominent. Toomer's grandfather, P.B.S. Pinchback, was the first African American elected governor of a state (Louisiana). In Washington, Pinchback served as a US Marshall and practiced law. His elegant home was the site of lavish parties. And yet Toomer preferred the seedier 7th Street district.

See #8 on the map: Working class 7th Street was a magnet for the many newly transplanted African Americans from the rural south.

The 7th Street neighborhood was home to small restaurants, pool halls, barbershops, and juke joints. In Cane, Jean Toomer offered a lively description of the area that captures both its appeal and its disturbing history:Seventh Street is a bastard of Prohibition and the War. A crude-boned, soft-skinned wedge...breathing its loafer air, jazz songs and love, thrusting unconscious rhythms, black-reddish blood into the white and whitewashed wood of Washington. Stale soggy wood of Washington...White and whitewash disappear in blood. Who set you flowing? Flowing down the smooth asphalt of Seventh Street, in shanties, brick office buildings, theaters, drug stores, restaurants, and cabarets? Eddying on the corners? Swirling like a blood-red smoke up where the buzzards fly in heaven? God would not dare to suck black red blood...He would duck his head in shame and call for the Judgment Day. Who set you flowing?

Cane was a mixture of poetry and short fiction. The first and third sections were set in Georgia, but the middle part was inspired by 7th Street. Langston Hughes, influenced by the book and defiantly acting in reaction to his pretentious cousins, began to spend his free time in the neighborhood. In The Big Sea, he wrote:

Seventh Street is the long, old, dirty street, where the ordinary Negroes hang out, folks with practically no family tree at all, folks who draw no color line between mulattoes and deep dark-browns, folks who work hard for a living with their hands. On Seventh Street...they played the blues, ate watermelon, barbeque and fish sandwiches, shot pool, told tall tales, looked at the dome of the Capitol and laughed out loud.

The number of jobs Hughes managed to go through in his very short time in Washington is evidence to his unsettled state of mind. He worked briefly in a restaurant shucking oysters (name and location unknown). He wrote:

...I got a job at a fish and oyster house in downtown Washington. (I always liked jobs in places where you eat.) I wore a tall white cap...and I stood behind a counter twelve hours a day, making oyster stews and oyster cocktails to order. My first week there I ate so many oysters myself that I broke out all over in an oyster rash.

His next job was at the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History as an assistant to Dr. Carter G. Woodson. Hughes worked on proofs of the book Free Negro Heads of Families in the United States in 1830, and was paid $55 per month.

See #6 on the map: The site of this office, acquired by the National Park Service but not yet open to the public, is marked with a historic plaque (located at 1538 9th Street NW).

In an essay, "When I Worked for Dr. Woodson," Hughes recalled Dr. Woodson's unstinting work ethic:One never got the idea that the boss would ask you to do anything that he would not do himself. His own working day extended from early morning to late at night. Those working with him seldom wished to keep the same pace...we all respected him greatly and admired his ever-evident devotion to the work he was doing, the history he brought to life, and the racial cause he so well served. We often said, sometimes with envy, that if we could work that hard we might get somewhere someday too. But none of us really wanted to work that hard...

He described his duties in The Big Sea:

I had to go to work early and start the furnace in the morning, dust, open the office, and see that the stenographers came in on time. Then I had to sort the mail, notify Dr. Woodson of callers, wrap and post all book orders, keep the office routine going, read proof, check address lists, help on the typing, fold and seal letters, run errands, lock up, clean the office in the evening—and then come back and bank the furnace every night at nine!...Although I realized what a fine contribution Dr. Woodson was making to the Negro people and to America, publishing his histories, his studies, his Journal of Negro History, I personally did not like the work I had to do. Besides, it hurt my eyes. So when I got through the proofs, I decided I didn’t care to have “a position” any longer, I preferred a job...

One of the most significant aspects of Hughes's time in Washington was his participation in the Saturday Nighters Club, a literary salon at the home of Georgia Douglas Johnson, nicknamed “Half-Way House.” Gathering weekly for cake, wine, and stimulating discussions, this literary salon brought together the Washington contingent of the Harlem Renaissance, giving the era's young, ambitious writers a chance to mingle with older mentors. Regular attendees included: Kelly Miller, dean of Howard University; his daughter, the playwright May Miller; critic and anthologist Alain Locke; historian Carter G. Woodson; Angelina Weld Grimké, the author of the first play by an African American to receive a fully-staged, professional production; writer and actor Richard Bruce Nugent; essayist and playwright Marita Bonner; poet and short story writer Alice Dunbar Nelson; Jean Toomer; and Zora Neale Hurston.

See #9 on the map: The Georgia Douglas Johnson house still stands at 1461 S Street NW, a private residence, marked with a plaque.

The Johnson House is one of the most important extant sites of the Harlem Renaissance. Jessie Redmon Fauset wrote to Hughes on August 3, 1925:I’m so glad you’re seeing Mrs. Johnson—she is so kind and charming and stimulating. I covet her disposition. Cultivate her—she will be balm to your troubled spirit.

In The Big Sea, Hughes described Johnson:

Georgia Douglas Johnson, a charming woman poet, who had two sons in college, turned her house into a salon for us on Saturday nights...[we] used to come there to eat Mrs. Johnson’s cake and drink her wine and talk poetry and books and plays....My two years in Washington were unhappy years, except for poetry and the friends I made through poetry. I wrote many poems. I always put them away new for several weeks in a bottom drawer. Then I would take them out and re-read them. If they seemed bad, I would throw them away. They would all seem good when I wrote them and, usually, bad when I would look at them again. So most of them were thrown away.

Hughes began to make connections with the New York contingent of the Harlem Renaissance through Johnson as well. When he won first prize in poetry from Opportunity magazine for “The Weary Blues,” he traveled to New York to attend an awards banquet, and pick up his prize money. At this event, Hughes was befriended by Carl Van Vechten, who arranged for his own publisher, Knopf, to give Hughes a contract for his first book.

Wanting to work on his manuscript full time, Hughes moved out of the apartment he was sharing with his mother and Kit to a room at the 12th Street YMCA. His mother made it very clear that she would not tolerate Hughes living with her while not working a job that could contribute to the family income.

See #3 on the map: The Y, now known as the Thurgood Marshall Center for Service and Heritage, still stands at 1816 12th Street NW, and includes a small museum with a recreated single-occupancy room such as the one Hughes would have rented.

The Y is a handsome building designed by W. Sidney Pittman, the first registered African American architect. Financed in part by John D. Rockefeller, President Roosevelt laid the cornerstone in 1908, and the building was completed in 1912 with rooms for 54 single-occupancy residents on the 3rd and 4th floors. Rooms were long and extremely narrow, with space for a twin bed and not much more.

But at the end of September 1925, broke and feeling desperate, and tired of skipping meals to save money, Hughes moved back in with his mother on S Street and took a job as a busboy in the Dining Room of the Wardman Park Hotel.

See #7 on the map: The earlier building has been razed, but a new hotel, the Marriott Wardman Park, was built on the same location, at 2600 Woodley Road NW.

In a letter to Carl Van Vecten (October 9, 1925), Hughes reported:The place I work is quite classy. There are European waiters and it caters largely to ambassadors and base-ball players and ladies who wear many diamonds. It is amusing the way they handle food. A piece of cheese that everybody else carries around in his hands in the kitchen needs two silver platters and six forks when it is served in the dining room.

This was the site of Hughes's first national recognition. He recounted the story in The Big Sea:

...I am glad I went to work at the Wardman Park Hotel, because there I met Vachel Lindsay. Diplomats and cabinet members in the dining room did not excite me much, but I was thrilled the day Vachel Lindsay came. I knew him, because I’d seen his picture in the papers that morning. He was to give a reading of his poems in the little theater of the hotel that night. I wanted very much to hear him read his poems, but I knew they did not admit colored people to the auditorium.

That afternoon I wrote out three of my poems, "Jazzonia," "Negro Dancers," and "The Weary Blues," on some pieces of paper and put them in the pocket of my white bus boy’s coat. In the evening when Mr. Lindsay came down to dinner, I quickly laid them beside his plate and went away, afraid to say anything to so famous a poet, except to tell him I liked his poems and that these were poems of mine. I looked back once and saw Mr. Lindsay reading the poems, as I picked up a tray of dirty dishes from a side table and started for the dumb-waiter.

The next morning on my way to work, as usual I bought a paper—and there I read that Vachel Lindsay had discovered a Negro bus boy poet! At the hotel the reporters were already waiting for me. They interviewed me. And they took my picture, holding up a tray of dirty dishes in the middle of the dining room. The picture...appeared in lots of newspapers throughout the country. It was my first publicity break.By this time, with the help of Carl Van Vechten, Hughes had sold six poems to Vanity Fair, which appeared in the September 1925 issue. He published poems soon after in the New Republic and Bookman. Although the monetary amounts he earned from these publications was small, Hughes was encouraged. He also won a poetry award from The Crisis magazine. Hughes wrote:

Jessie Fauset at the Crisis, Charles Johnson at Opportunity, and Alain Locke in Washington, were the three people who midwifed the so-called New Negro Literature into being. Kind and critical—but not too critical for the young—they nursed us along until our books were born. Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, Arna Bontemps, Rudolph Fisher, Wallace Thurman, Jean Toomer, Nella Larsen, all of us came along about the same time.

Hughes gave his first public poetry reading before a white audience at the Penguin Club in late August or early September. The Penguin club no longer stands (the site, at 1712 I Street NW in the Farragut Square neighborhood, is now a high rise). In a letter to Carl Van Vechten of September 7, 1925, Hughes wrote:

I got along fine with my Penguin Club reading. At least, the people said I did. I met a former cabinet minister and a friend of Sara Teasdale’s and a few other important humans. There was quite a crowd and if I had not been the center of attraction I would have been amused.

At the end of 1925, Hughes, while riding a streetcar, met Waring Cuney, a DC native and young poet. Cuney told him about Lincoln University (near Philadelphia), the oldest African American college in the country, where he was a student. Cuney and Hughes quickly became close friends, and Hughes decided to apply. Amy Einstein Spingarn (wife of a prominent NAACP leader, Joel Spingarn) agreed to finance Hughes’s education at Lincoln.

In January 1926, The Weary Blues, Hughes's first book, was published by Alfred A. Knopf. Hughes gave a pre-publication reading at The Playhouse, a private club, on January 15. Admission to the event was $1 per person; Hughes was introduced by Alain Locke, who described the poems in the forthcoming book as having “...a distinctive fervency of color and rhythm, and a Biblical simplicity of speech that is colloquial in derivation, but full of artistry.”

See #10 on the map: The Playhouse still stands at 1814 N Street NW, near Connecticut Avenue, south of Dupont Circle. It is now office space.

Hughes entered Lincoln University in February. He did not return to DC, except for six brief visits (to see Ezra Pound, incarcerated at Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital for the Criminally Insane, in 1950, to testify at the McCarthy hearings in 1953, and on four other occasions to give readings of his work).

Although Hughes found DC's African American community oppressive, and he was happy to escape to college (and then to Harlem), in many ways his short time in Washington permanently influenced his thinking and his writing. It was here that he first cast his lot with the working class, and his time spent on 7th Street awakened his political sensibilities. Certainly the blues music he heard in DC juke joints suggested a new form for his poems. Class would forever be intertwined with his poetic expression from this point forward.

Kim Roberts is editor of Beltway Poetry Quarterly and author of three books of poems, most recently Animal Magnetism, winner of the Pearl Poetry Prize (Pearl Editions, 2011). She is editor of the anthology Full Moon on K Street: Poems About Washington, DC (Plan B Press, 2010) and author of the nonfiction chapbook Lip Smack: A History of Spoken Word Poetry in DC (Beltway Editions, 2010). She has published articles and walking tours on several writers with ties to DC, including Walt Whitman, Zora Neale Hurston, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, and in 2010 the Humanities Council of Washington commissioned her to create a web exhibit, "Wide Enough for Our Ambition," on the history of DC's segregated African American schools. She is the recipient of the Washington On-Line Award, the Independent Voice Award from the Capital BookFest, and residency grants to twelve artist colonies. Her website: http://www.kimroberts.org.

Published in Volume 12, Number 1, Winter 2011.

To read more by this author:

Kim Roberts

Roberts on Walt Whitman: Memorial Issue

Roberts and Dan Vera on DC Author's Houses: Forebears Issue

Kim Roberts on Bethel Literary Society: Literary Organizations Issue

Kim Roberts on DC Poetry Anthologies: Literary Organizations Issue